Planning forward: whole system support for marginalised learners in higher education

Steps towards taking a whole system approach to developing higher education that supports marginalised learners, thinking inclusively from the outset

Strengthening education systems holistically has been a part of the United Nation’s (UN) refugee education strategy since 2018. It is a key component of scaling to provide 15 percent of refugee youth with access to higher education by 2030, to move towards parity with the youth population globally.

Instructional Design for E-Learning (IDEL) began as part of the Connected Learning in Crisis Consortium, led by the UN Refugee Agency and Arizona State University, which works to promote greater access to blended and online learning for refugee students and their host communities.

IDEL started in 2019, training professors from universities in Jordan in effective online and blended course design and delivery. Since then, IDEL has expanded to work with the University Consortium for Quality Online Learning (UCQOL), a group of nine universities across the United Arab Emirates committed to leading the transition to quality online education.

- THE Campus spotlight: What universities can do to assist refugees

- Bridges to study: how to create a successful online foundation course

- How block teaching supports students from under-represented groups

Underpinning these efforts is the hope that improving education for everyone will create opportunities for marginalised learners to be included in these programmes – thinking inclusively from the start of design.

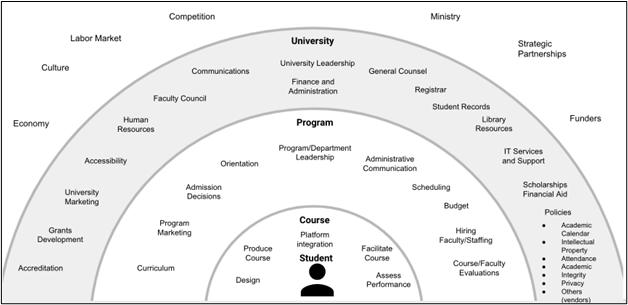

Building an inclusive education ecosystem that supports marginalised learners begins with strategy alignment among all stakeholders involved in meeting the needs of the students. A learner-centred approach requires an understanding of the diverse layers that constitute higher education and the forces acting upon administration, faculty and students within each layer.

The following factors have been critical to our approach:

Use a human-centred design approach to uncover the contextual layers within which students operate and reveal forces that impact their progress, in order to shape the learner journey. This helps form indicators to measure success at every stage of the student’s journey. Using design-thinking aligned to evidence-based pedagogical frameworks shifts thinking from “what does a student know” to “what will the student do with what they know”.

Traditional learning ecosystem models do not consider the complex, changing nature of education systems within society and the societal forces acting on the learner. For example, a refugee student might be enrolled in an engineering programme but not be legally able to work in their host country. Labour laws affect employability and thus whether a student can secure a livelihood. There are new opportunities for global remote freelancing. If I can be employed anywhere, what laws govern where I can receive a paycheck, whether or not I would have access to refugee services and how taxation may work for a refugee employee?

By capturing and building examples of student personas – ie, a young single mother working part-time to pay for study – you can run scenarios against university programmes to determine what additional systems and support are needed to lead to student success.

Thoroughly assess and identify the needs of the universities and their students within the ecosystem, ie, their financial needs, learning support needs, funding, instructional design needs, marketing and more. Consider the societal forces (social, political) within that system that they need to be aware of. What resources and capabilities can be leveraged, which gaps must be prioritised and which opportunities have the greatest potential?

Before launching a programme, a needs analysis at university level should examine existing resources within the institution. This should provide a comprehensive view of the university’s strengths, weaknesses, resources and capacity in order to identify assets and gaps, as well as potential barriers and opportunities for growth.

At the systems level, the analysis should examine the regulating (ministries and accrediting bodies), financial and economic (region, country and individual university) forces that impact the learner.

Considering regulatory bodies from the outset is vital to ensure ministry and accrediting support for e-learning and marginalised learners is developed along with university programmes.

Equally important is understanding financial obligations since universities operate through numerous funding mechanisms including central government, enrolment and external backers. An institution’s revenue structure dictates how many decisions are made, including hiring and training new faculty, moving to e-learning and the support resources that accompany these programmes. It will also dictate the budget for discretionary spending for scholarships and support for marginalised learners.

Map to known quality standards and international standards of practice at every opportunity. Find the relevant quality standards to guide your work when building frameworks for faculty training, designing and evaluating courses and assessing institutional readiness. For example, quality standards for course design can be found at Quality Matters (QM) and the SUNY Online Course Quality Review (OSCQR), among others.

Course design should focus on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles. UDL offers the learner a choice in the way they engage with learning materials, which are developed using varied formats and techniques, and in the way they demonstrate their mastery of a subject. For instance, instead of using a multiple choice test as a final assessment you may let the learner choose from three different options, such as a presentation, a project, or a poster.

Advocate for places for marginalised learners from the start so that the opportunities that are being created can benefit diverse populations, especially those who have been denied access to higher education such as the forcibly displaced. There are various ways to accomplish this, here are three examples:

- Create space within the budget for scholarships, reserve spaces for marginalised learners within programmes, waive tuition for marginalised learners and create positions for scholars at risk within the programmes.

- When developing new programmes with the help of third party providers such as IDEL, a university can negotiate to pay the provider “at cost”, only covering outgoings, rather than paying the usual commercial rates. In turn, the university would guarantee spaces or financial aid for marginalised and refugee learners as part of paying a lower rate - 'at cost', with a sliding scale of fees creating opportunities and placements.

- Advocating for marginalised learners can be made a condition of service for staff within a university and a formal part of the institution’s commitment to being socially responsible and to advance educational opportunities for all learners.

Calculate and budget the funding needed to enable transformation in all areas of education provision. Developing an online programme is more than simply building courses. Programme development involves training faculty and staff, recognising personnel gaps, investing in systems for learning and learner management, and creating effective communication and support channels. When donors invest in holistic programme development, they identify the true cost of educating a student. This means identifying funding vehicles that sustain long-term growth and development.

Identify and resource student support services to ensure the range of student needs are met. Services such as guidance on financial aid, registration, bridging programmes as well as access to the library, childcare, disability and counselling services are critical to the success of the student. The services for refugee and marginalised learners often extend beyond those anticipated for traditional or in-person learners.

Collaborate to leverage resources. Complex, dynamic, learning ecosystems are optimised by working collaboratively with stakeholders at all levels and sharing resources where possible. Solutions that scale require a diverse set of skills, and by partnering with other organisations it is possible to extend the reach of programmes and manage costs.

Education can be a catalyst for greater prosperity by focusing on the student and the complex learning ecosystems needed to guide them to success.

Carrie Bauer is programme director for Instructional Design for E-Learning (IDEL) and a former instructional designer at Arizona State University; Cindy Bonfini-Hotlosz is chief executive officer at Centreity; and Charley Wright is also chief operating officer at Centreity and a former connected learning specialist at UNHCR. All three authors are part of the Connected Learning in Crisis Consortium (CLCC).

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.